NASA weighing lunar lander budget options

NASA weighing lunar lander budget options

WASHINGTON — NASA is looking at ways to stretch out the budget for its Human Landing System program should there be further delays in a final appropriations bill while still seeking full funding for the program in 2021.

Funding for the HLS program, which supports development of commercial landers to carry astronauts to and from the lunar surface, has become a major uncertainty in the ability of NASA’s Artemis program to achieve the goal of landing humans on the moon by 2024. NASA requested $3.2 billion for the program in its fiscal year 2021 budget proposal. However, a House bill passed in July provided only about $600 million, while the Senate has yet to release its version of a spending bill.

HLS, like the rest of NASA and other federal agencies, is operating under a continuing resolution (CR) that funds it at 2020 levels since the 2021 fiscal year started Oct. 1. That CR runs through Dec. 11, with the expectation that Congress will take up a full-year 2021 omnibus spending bill after the Nov. 3 general election. The outcome of the election, and its timing, could affect what kind of spending bill Congress would consider and when.

That uncertainty does not affect ongoing work with the HLS program, with three companies — Blue Origin, Dynetics and SpaceX — working on lunar lander designs under 10-month “base period” awards NASA made in April. Those three awards have a combined value of $967 million.

“Right now our base period goes through February 28, and we are funded to complete all the base period milestones,” Lisa Watson-Morgan, HLS program manager at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, said during an Oct. 26 session of the American Astronautical Society’s Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium.

The situation is less clear, though, if 2021 spending isn’t resolved by then. Watson-Morgan said the program planned “some interesting methods” that could buy the program an additional month or so. She didn’t elaborate on those methods, but noted they take advantage of the fact that the HLS awards were made under a broad agency announcement through the Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships (NextSTEP) initiative.

Beyond that, she said, “we could delay month by month,” but warned the agency risked losing some of the companies in the program. “These industry partners that you see here have other work that they’re going to have to go off and do, that they’re getting paid to do,” she said. “It’s important that we match up both the funding and the work to make sure that we can continue this progress.”

She did not explicitly state what would happen to the HLS program if the House funding level of about $600 million made it into the final spending bill, but reiterated comments by others at NASA, including Administrator Jim Bridenstine, that NASA needs the full $3.2 billion to keep a 2024 landing on track. “We are certainly also planning to get additional funding so that we can achieve the moon landing in 2024.”

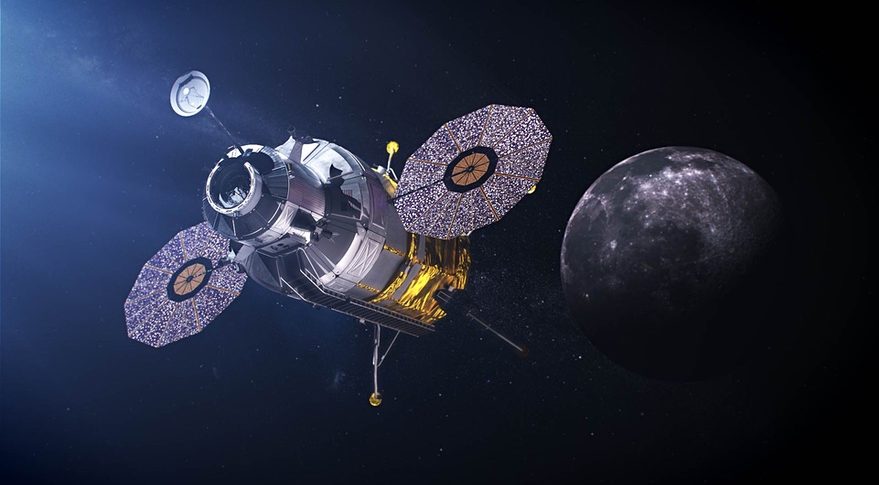

Watson-Morgan appeared on a panel with representatives of the three companies in the HLS program. They primarily offered overviews of their proposed landers, with little in the way of updates about the progress they have been making on their designs since winning the initial HLS awards in April.

NASA announced Oct. 22 that all three companies had completed certification baseline reviews, where NASA and each company confirmed lander development plans and agreed upon standards that will guide work on the lander. NASA also said that it is running an “active federal procurement” for HLS Option A, where the agency will award contracts to up to two companies to work on landers that could support a 2024 landing.

The certification baseline reviews were “incredibly successful,” Watson-Morgan said, “and now we’re preparing for the continuation reviews” where NASA will select the two companies to proceed with full-scale lander development.

She said keeping two companies in the program after the continuation reviews was important. “Having two U.S. industry partners competing for that first slot to go to the moon will get us there faster,” she said, because of competition.

That competition, though, may be why the companies were reticent to share many details about their work. “Since we are still in a competitive mode, there’s only a limited about of information that is publicly available, because we want to make this as fair and as honest a competition as possible,” she said. “Next spring we should be wide open, ready to tell all, share all.”

Comments

Post a Comment